Our Miss, Behave! collection is inspired by the kind of women you want on your side, the kind of women you’d like to be. And despite what you didn’t learn in school, there are enough of their stories to fill stacks and stacks of history books. We know you’ll love our muses and their stories as much as we do, so we wanted to share a few here. Niki de Saint Phalle’s had to be one of them, not only because of her fascinating life but because since we serendipitously encountered her work at the Bechtler Museum of Modern Art, we’ve been in love with its playful approach to the arcane.

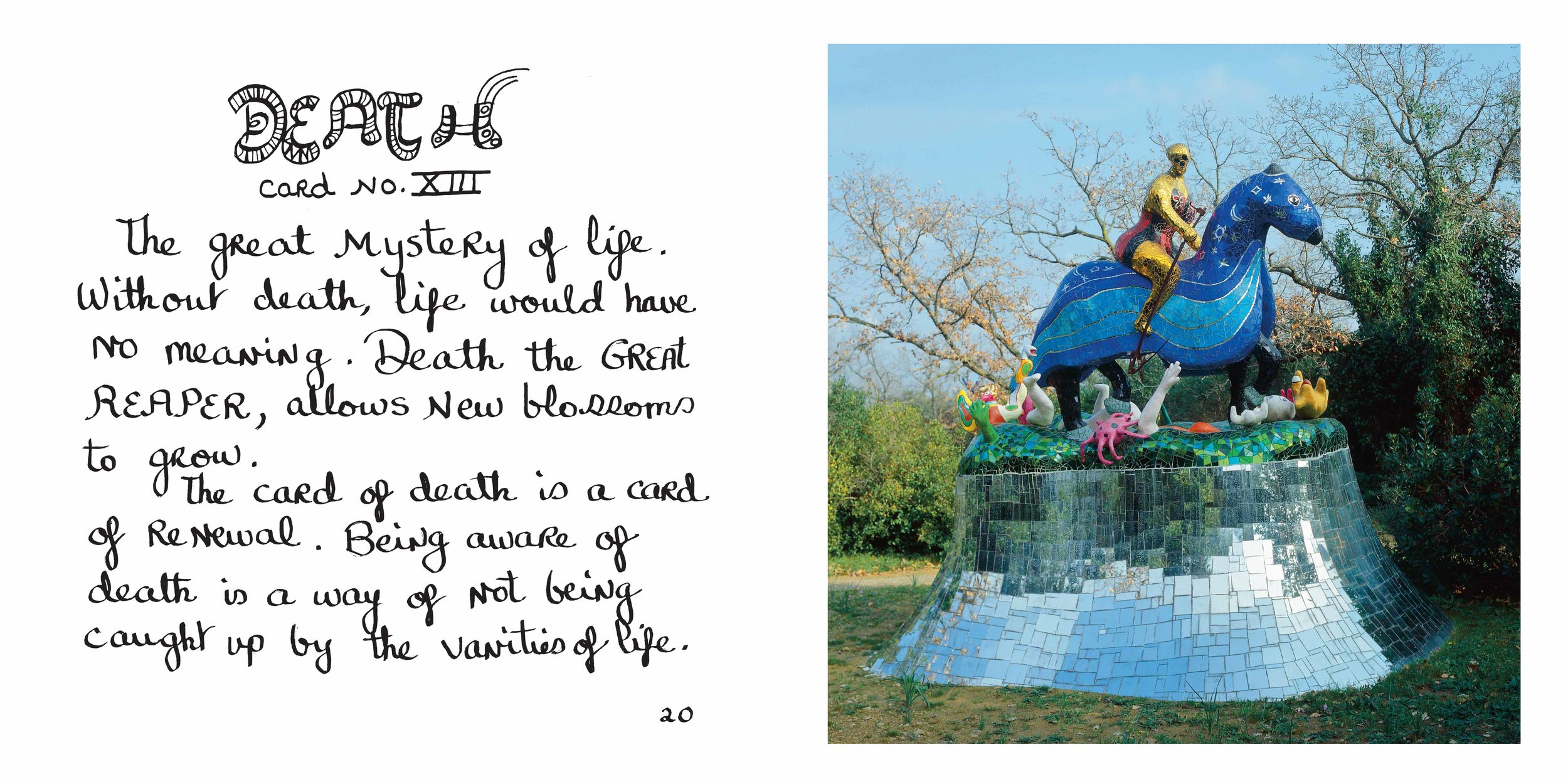

With her typical dramatic flair, during the last years of her life Niki de Saint Phalle made her home in a gigantic sculpture of The Empress from the tarot's Major Arcana. The center of her Tarot Garden, her magnum opus located in the Tuscan countryside, The Empress is a huge, heavy breasted figure complete with a mirrored interior which includes a bedroom, living room, and kitchen. Populated with enormous mystical figures made up of undulating lines, found objects, shattered mirrors, and pottery mosaics, the Tarot Garden was described by Saint Phalle as “a sort of joyland where you could have a new kind of life that would just be free.” Her personal route to that kind of freedom would be as circuitous as one of her sculptures.

The Empress (clockwise from top) exterior, dining room, and door detail

Saint Phalle was born into an aristocratic French family in 1930 and within months of her birth, her French father lost his wealth when the Great Depression spread to Europe. The family moved to the US, where her mother had been born, leaving their infant daughter behind with her grandparents until she was three. The relationship between Saint Phalle’s parents and their children was marked by a mixture of apathy and what might have then been termed discipline, and today defined as abuse.

When she was old enough for school, her parents settled Saint Phalle into a tenure at various religious boarding schools where her time was fraught with discord. (She was expelled from one for painting the fig leaves on all of their Grecian marble statues a bright red.) She began a modeling career at 17, and at only 18, she married a childhood friend as a way to escape her family and her father’s sexual abuse, which haunted her mind and her work for the rest of her life. She would spend years exorcising the demons created by her father’s trying to “make her his mistress” when she was 11, by her mother’s coldness and distance, and by the strictures imposed on her in their conventional home and in their world.

Her marriage to Harry Mathews began happily enough, but with financial challenges when his wealthy family all but disowned him for marrying a Catholic. By all accounts, Saint Phalle was ill-prepared for life as an American housewife, ignoring housekeeping duties that would have fallen to her as a matter of course. The couple soon had two children, who were often as neglected as the other chores, thanks to the couples’ sheer ignorance about childcare.

When Mathews inherited some money, the family moved to Paris, where they fell into a bohemian lifestyle that was the polar opposite of Saint Phalle’s Catholic parents’ strict rules. They mingled with a set of young musicians, writers, and artists, moving frequently to various towns across Europe, while Mathews pursued a literary career. The marriage began to disintegrate, with affairs on both sides, and the strain of it all led Saint Phalle to a suicide attempt, after which she was temporarily institutionalized. In the asylum, she found that art would be her solace and salvation. (If that sounds like an overstatement, consider that both of her younger siblings died by suicide as adults.)

From top left: wedding to Harry Mathews, with Harry and daughter Laura, Self Portrait 1958, Be My Frankenstein 1964

After her six weeks in the sanatorium, Saint Phalle and Mathews took up their peripatetic lifestyle again, but she had a new focus to sustain her -- her artwork. She was constantly working on collages and paintings, and when they returned to Paris, she took a small studio. There, her work brought her into contact with kinetic sculptor Jean Tinguely, part of the Nouveau Réalisme group which also included Yves Klein. Tinguely, who was in an open marriage himself, became friends with the couple who were also trying to salvage their relationship by loosening the strictures of traditional marriage. It was to no avail. Saint Phalle realized that she couldn’t fit herself into the role of wife and mother, and that her art had to take precedence for her sanity. In 1960, after twelve years of marriage, she announced to Mathews that she was leaving, and she moved into her Paris studio.

Within months, she began a relationship with Tinguely that would last for the rest of his life; for thirty years, he was a lover, a friend, a co-creator, and (briefly) her second husband. Soon, Saint Phalle took the art world by storm with her shooting paintings, in which she exorcised her feelings by performative events in which she took aim at canvases constructed of plaster, found objects, and bags of paint. When shot, the paint burst and created patterns across the white plaster surface. The sight of the beautiful young woman, often dressed in a body conscious white jumpsuit, aiming a rifle at her representation of the patriarchy drew crowds and reporters in cities across the globe, as did her collaborations with prominent artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg.

Clockwise from top middle: in Paris with Jasper Johns 1961, dressed up for filming her shooting painting, shooting painting from her 1960 - 1963 Tirs series, detail from a completed shooting painting.

Clockwise from bottom left: with a group of male artists (Olov Ultvedt, Robert Rauschenberg, Martial Raysse, Daniel Spoerri, and Jean Tinguely) 1962, Saint Phalle works on a Nana while Tinguely watches 1966, Saint Phalle and Tinguely 1960s, Saint Phalle and Tinguely 1963

Through the years, Saint Phalle’s work evolved into the fantastic oversized creations for which she is most famous. She and Tinguely often worked on pieces together and shared exhibits, but it was on an equal footing and neither found their identity subsumed into that of the other during their long partnership. Saint Phalle became famous for her Nanas, huge, curvy female figures with brightly painted surfaces. Hon, her multiple room-sized version of the Nana, was installed temporarily in Stockholm in 1966. Museum-goers entered between the legs of the reclining figure to find a cinema and a museum of fake paintings (among other things). Tinguely was instrumental in creating the rebar skeleton that supported Saint Phalle’s vision, as he would be for many other pieces including the Tarot Garden.

Clockwise from Left: Untitle Nana Fountain Figure 1999, Black Dancing Nana on metal base by Tinguely 1970, Red Nana Vase 1993

Hon sketch and patrons at the installation in the Moderna Museet of Stockholm 1966

In 1955, Saint Phalle had visited Barcelona and encountered the works of Gaudi, which sparked a vision of a huge sculpture garden that wouldn’t be realized until the ‘70s. She wanted to “show that a woman can work on a monumental scale” as she wrote in a letter, but her work didn’t get started until 1974 when she reconnected with an old friend from her modelling days whose aristocratic family gave her the 14 acres of land in Tuscany for the garden. The plan for the Tarot Garden included 22 sculptures of the figures from the Major Arcana, some over sixteen yards tall. Built of concrete poured over a framework made of steel rebar and wire mesh, the figures were then finished with tile, mosaics, quotes, and the whimsical decorative painting style for which Saint Phalle’s Nanas were so famous. After years of planning, in 1979 construction began, involving a huge team made up of mostly men, to whom Saint Phalle became a den mother of sorts. Tinguely and Swiss artist Rico Weber, who had worked with them on Hon, worked on the rebar structure, and a rotating team of artists and locals were recruited to complete the mammoth project.

A view of the Tarot Garden and mosaic details

In addition to her work on the project, Saint Phalle was continually raising funds to keep it going. She released a fragrance in a signature bottle and even sold inflatable versions of her Nanas. Although she was criticized for these decisions, nothing was sacred when it came to the completion of her garden. The park was opened to the public in 1998, and work continued until her death in 2002, at the age of 71. For years, Saint Phalle had suffered from rheumatoid arthritis, sometimes so bad she could hardly walk, and her work with the polystyrene she used in her sculptures led to severe lung problems. Saint Phalle sacrificed her marriage, motherhood, and her health to her artistic vision. Today, the figures of the Major Arcana stand as her unique and whimsical monument in the Tuscan countryside, where they are visited by 75,000 people a year.

TLDR version: Niki de Saint Phalle exorcised her demons into oversized mythical creations whose surfaces covered with mosaics, messages, and found objects transformed childhood fear into childlike freedom.

Ganesh, 1993

The Empress, the fragrance inspired by Niki de Saint Phalle, highlights notes of bubblegum, lush gardenia, Bulgarian rose, and dragon’s blood incense shattered and soaked in amber honey. Our favorite work of hers is a small sculpture of a Ganesh with a bubblegum pink body and a crown of electric lightbulbs, so it seems fitting that the bubblegum accord should represent the nostalgia and wonder of childhood so prominent in her later works. Shared chemical components with the florals lead the way to a heart of sweet gardenia flower and a fruity pink rose. There is something unabashedly feminine in Saint Phalle’s work and persona -- the curves, the hearts and flowers, the way her Nana sculptures evoke fertility goddesses -- just like the floral heart of this fragrance, which conjures up velvety petals and their intoxicating scent. But there’s more to her work than sweetness and fun! The dragon’s blood incense and deep amber honey evoke the mystical, the elemental. If you’ve ever burned the resin, you know that dragon’s blood is aptly named, bubbling up in the most shocking red while it spreads its rich, spicy scent. In The Empress, we tried to capture an encounter with Saint Phalle’s work, the initial fun and childlike sweetness engaging your attention until you discover that you’re experiencing something deeper, maybe even magical.

If you’d like to learn more about Saint Phalle, don’t miss the epic 2016 New Yorker article, Beautiful Monsters. You can also check out her Tarot Garden site, which features some of her own thoughts about the work, as well as a helpful chronology. Hyperallergic’s coverage of a 2015 Paris exhibit offers further insight into her body of work. There are a few documentaries available on YouTube, which range in quality. Niki de Saint Phalle Introspections and Reflections is an English language documentary; it’s thorough and includes some great quotes and shots of her work, especially outdoor sculptures and kinetic works, but the narration is a bit dull. Even if you don’t speak French, the French language documentary of Saint Phalle and Tinguely is worth watching for its interviews and footage of the couple (some of which is in English). If you’re lucky enough to be a German speaker, there’s a charming German language film with great production values and less of the grainy quality that plagues the older versions. Whether you came here looking for more information about Saint Phalle, or you've just discovered her through our collection, we hope that you'll fall in love with the artist and her work as much as we did.